The Arithmetic of Tariffs and Their Impact on Inflation

Subdued inflation as producers absorbed the costs through lower labour expenses and profits, but ultimately, prices will rise, hurting consumers, with implications on Fed's rate cuts and asset prices

One driving force (if not the driving force) moving markets is the expectation that major central banks (read: the Fed) will continue to cut policy rates. The main reason: the economy is softening and, crucially, inflation is moderating, trending to the policy target.

To that end, one lingering and puzzling question for many (me too!) is what happened to the expected impact of the increase in tariffs on inflation. In fact, despite the zigzagging, overall tariffs have indeed increased in the U.S. from about 2.3% in 2024 to ~16% currently; sizable, right? So, where is the widely expected impact on prices?

Chart 1: US effective tariff date

The typical narrative is that the impact on prices is “about to happen.” But we have been waiting since “Liberation Day” in April, and nothing meaningful has happened, leading some to conclude that tariff increases (even of that magnitude) have had no meaningful impact on prices and have been fully absorbed by the various actors.

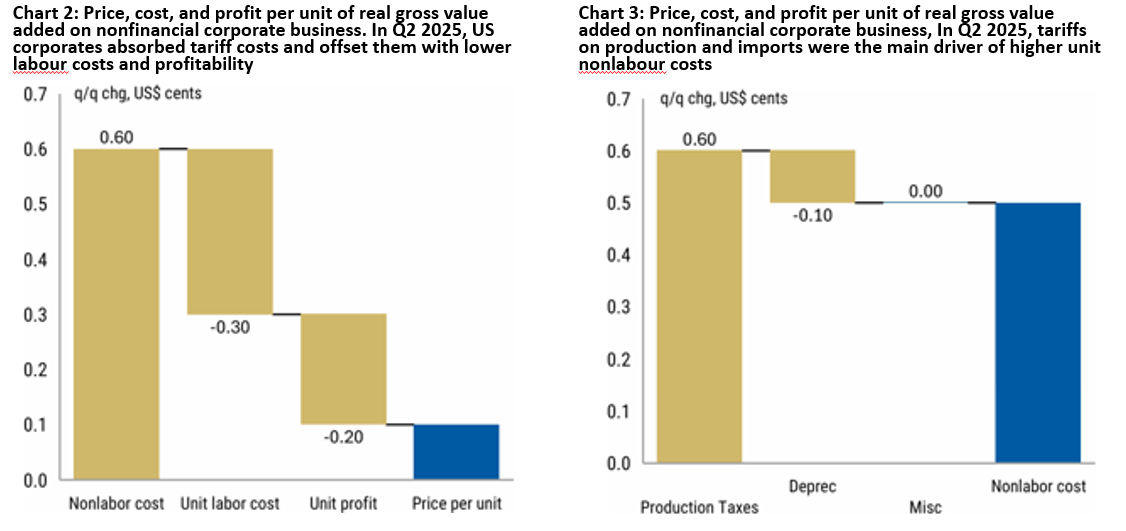

Not so fast! Morgan Stanley did a very good job scrutinizing audited National Accounts data … that is, hard-core evidence, no opinion. The conclusion: tariff increases have been absorbed by a reduction in unit labor costs (about half), a reduction in unit profits, and only a very small increase in prices (see graph below). Going forward, this is clearly untenable, given that either profits (and EPS) will eventually decline, or prices will eventually go up; in both cases, the economy will shrink, with declines in production and consumption, i.e., the potential for stagflation is alive and well! Feds beware!

“Another” narrative (primarily touted by the US Administration) is that tariffs have been fully absorbed by exporters to the U.S. This, too, however, is fully rejected by hard-core evidence, or the import price indexes. Indeed, most—if not all—trade is denominated in U.S. dollars. Tariffs could cause exporters to the U.S. to reduce their selling prices, thereby reducing U.S. import prices. Working against this, however, is the weaker dollar, which could instead mean higher import prices for U.S. firms. So, with a ~10% dollar depreciation right now, the potential effect of lower prices by exporters, if actually there, may have been offset, at least in part, by the FX move. The proof—still from National Accounts—is that import price indexes are, practically and on average, flat (see graph below).

So, the idea that tariffs will be “paid” entirely by exporters is simply not supported by the import price indexes, leaving the other two channels for the pass-through as the main conduit for tariff absorption: a tax on producers and/or a tax on consumption. And given that producers (and labor) have done whatever it takes to avoid passthrough to prices as described above, the next impact should logically be felt by consumers, with obvious implications for inflation, monetary policy, market valuations, etc.

With market expectations settled on two cuts by the Feds before the end of the year justified by moderating inflation, the room for disappointment and market corrections is “a real and present danger”.

Simon Nocera, Lumen Global Investments LLC

October 14, 2025